The town of Oberlin, OH was essentially built on a swamp. Oberlin basements commonly experience water problems. When we first purchased our Oberlin home in 1988 there were a few storm events that left water puddles in our basement. Various measures eliminated this problem, but high summer humidity remains an issue. For years we have employed a basement dehumidifier to prevent mold and mildew.

Our house in Maine also has humidity issues. We are on the Atlantic coast where the relative humidity is always above 70%. Both our house and guest cottage are built on granite ledge sloping down to the water. I wouldn’t have thought so, but it turns out the granite ledge is relatively porous to water flow. After every rain storm, water flowing down the hill towards the river creates water issues in our crawl spaces. Dehumidifiers have proved to be important to prevent condensation on our water pipes and mildew on the wood.

I have read that you need to keep the relative humidity level in your crawl space below 60% to prevent problems. The usual way to accomplish this is to 1) prevent water from entering the crawl space using water and vapor barriers, and 2) use a dehumidifier to remove what water does enter.

I have three dehumidifiers located in 1) our guest cottage crawl space, 2) house basement/crawl space, and 3) our Oberlin house basement. All three are plugged into smart plugs that record their energy use. The two Maine units are commercial units from AlorAir and the Oberlin one is a Honeywell residential unit.

In Oberlin I have a heated basement, so the dehumidifier never has to remove water from cold air. The Honeywell unit can handle that. I do not run it during the winter. In contrast, the Maine crawl spaces are not heated and get quite cold. The AlorAir commercial dehumidifiers can remove water even when the air temperature is in the 40’s. I ran both of them last winter — not sure if I need to and will try to figure that out.

The graph below shows they day-to-day energy use of our guest cottage. As the graph shows, the dehumidifier uses 4-5 kWh of energy daily.

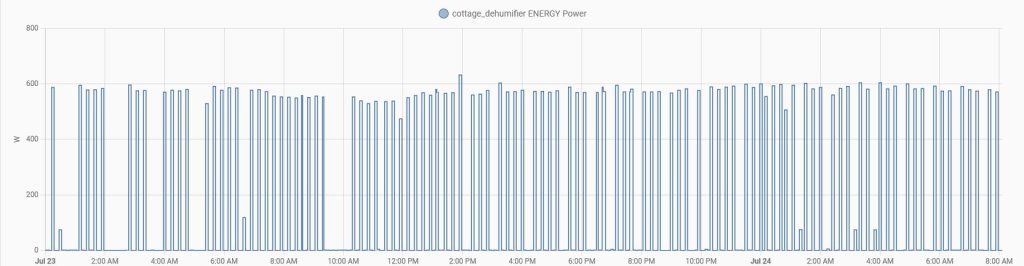

The AlorAir unit uses 600 W when the compressor is running. I normally leave its set point at 60% relative humidity and the compressor cycles on and off. A typical graph of its power vs time is shown below.

When I lower the set point the duty cycle increases (i.e., time that the compressor is on is longer) and the daily energy increases — all as expected.

I am a bit worried about the frequent cycling of the above dehumidifier. I don’t understand why the control doesn’t include a larger “deadband” so that the compressor does not switch on and off so frequently. I attempted to reach out to AlorAir to learn more but I found their technical support to be unresponsive.

The first graph above shows that the dehumidifier used much more energy on July 17. The reason for this is that I decided to try cooling the guest cottage air by circulating it through the crawl space. This exposed a continuous source of humid, warm air to the dehumidifier and it ran nearly continuously. After one day I concluded this was not the optimum way to cool the cottage.

The average energy used by the dehumidifier in my Maine house for July has been 3.4 kWh/day. The area of the house crawl space is larger than that of the cottage, but it is better sealed. Unlike the cottage the crawl space floor in the house is fully sealed with concrete.

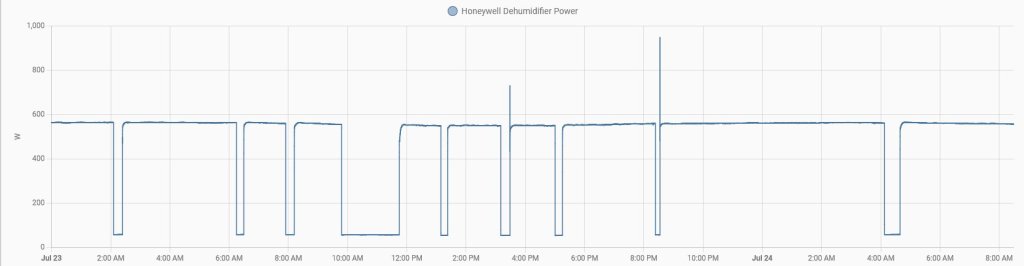

The average energy used by the dehumidifier in in Oberlin for July is about 12 kWh per day. Our house there is over 100 years old and all the walls lack modern vapor barriers. The graph below shows the power used by this dehumidifier. This unit removes about 60 pints of water daily and runs almost all the time during the summer.

This dehumidifier is about a year old. My experience with these “basement units” is that they work well for a few years. After a few years they continue to use lots of energy but don’t remove much water. When I bought this Honeywell unit last fall, the dehumidifier it replaced was 4 years old. I ran the two of them side by side for a few days and found the new unit removed water at a rate 5X that of the old one (even though they had the similar specs and were using similar energy). It is hard to throw the old one away because it still removes water — just not good at it.

What I don’t know is the importance of keeping the relative humidity of my Maine crawl spaces low in the winter. My instinct is to believe that mildew and mold won’t grow during the winter in my cold crawl spaces even if the relative humidity is high. But when the temperature warms in the spring I need to keep the humidity level below 60%. But this is just a hypothesis. So far I am erring on the side of caution and running the dehumidifiers year round. They just use less energy in the winter.

I would like to reduce the energy and carbon emission associated with dehumidification. That would be accomplished by raising the relative humidity set point on the dehumidifier. But under no circumstances can I tolerate mold or mildew. I would be interested in learning what people have to say about this issue for cold and warm weather. Is RH% a relevant metric when the air temperature is low as is the case in the winter? Does it make sense to use lots of energy to achieve 60% relative humidity in a crawl space whose temperature is below 45F? I don’t know the answer to these questions and would value informed input.