In my previous post I mentioned that my mini-split heat pumps are clearly lowering carbon emission, as compared with alternate ways I might heat my house. Here is the justification for that conclusion.

First, Maine has a relatively low carbon electric grid. It does not come cheap. Maine has some of the highest electric rates in the country. On average I pay $0.23/kWh for my electricity.

The EPA e-grid web site lists the following characteristics for the electric grid in this region. You really have four different ways of thinking about it — and I will tell you which I believe is the best way. First, organized by state Maine’s electricity has a footprint of 0.311 lbs CO2/kWh of electric energy. Second, we are part of the NEWE e-grid sub-region. That sub-region is listed as having 0.537 lbs Co2/kWh. Third, Maine is contained in the NPCC Nerc region which is listed as having 0.506 lbs CO2/kWh. And finally, our grid is part of the New Brunswick System Operator Balancing Authority which has a carbon footprint of 0.169 lbs CO2/kWh. (The New Brunswick Canada grid is almost entirely powered by hydro.)

It is difficult to know which of these numbers better reflects the carbon footprint of electricity I buy from the grid. Let me use the most conservative number of 0.537 lbs/kWh. Below I will offer yet another figure that I believe is more reflective of the true situation.

Consider propane heat as an alternative. Propane has a heat content of 91,500 Btu/gal. The carbon emission from burning a gallon of propane is 12.7 lbs/gallon. Most propane heating systems are 80% efficient (i.e., lose 20% of the heat up the chimney) although condensing furnaces can be as high as 92% efficient.

Consider the home heating oil alternative. Home heating oil has a heat content of 137,500 Btu/gal. The carbon emission from burning a gallon of home heating oil is 22.5 lbs/gallon. Depending on the age of the unit efficiency can range from 70-92%. Google reported home-heating oil furnaces can be as high as 99% efficient, but I don’t believe that for one minute. That was probably obtained with AI from a middle-school science report posted somewhere on the web. At best I would say 90% efficiency.

Finally, consider natural gas as an alternative. Natural gas is not available in rural Maine, but is available in some cities including Portland, Lewiston, Bangor, and Brunswick. Natural gas is, of course, widely available in many other states — but the comparisons presented here apply only to Maine’s electric grid. Natural gas heat content of 1038 Btu/cf. The carbon emission from burning a cubic foot of natural gas 0.121 lbs/cf. Like for home heating oil natural gas efficiency ranges from 70-92%. Most new natural gas boilers and furnaces are close to 90% efficient.

The final number to required is the conversion between kWh and Btu energy units. That conversion is 1 kWh = 3,416 Btu.

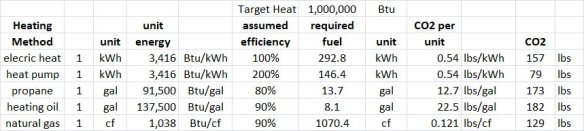

Here I assumed reasonable efficiencies for the various systems. Certainly older heating systems will be even less efficient.

Here we consider five heating systems listed in the table below. The question is how much CO2 do they emit (directly, or indirectly) in producing 1,000,000 Btu of heat. The calculations are easily accomplished with a spread sheet, and are shown in the table below.

What the table shows is that the electric heat pump with COP = 2 (200% efficiency) has the lowest carbon footprint — again, using a conservative estimate of the carbon footprint for the Maine electric grid. The next lowest carbon footprint would be for a 90% efficient natural gas boiler or furnace. This option is not readily available in rural Maine. Resistive electric heat has double the footprint of the heat pumps, but using Maine electricity, still has lower carbon than propane or a system that uses home heating oil.

Bottom line, given the various heating systems available to me, my heat pumps have the lowest carbon footprint — at least with the assumptions I have used.

I must point out, however, that you could look at the carbon footprint of the electric grid differently. Maine’s electric grid is what it is. My adding the load of a heat pump to the existing grid means that the load goes up. How is that load met? Given the economics of power the grid is always using generators with the lowest marginal cost of operation. So renewables are being maxed out, as is hydro and nuclear. If you need more power at any point it is obtained by ramping up a natural gas peaking plant. So the argument could be made that additional load on the grid has the carbon footprint of a natural gas peaking plant — which is much higher than the carbon footprint.

Again, the basic argument is this. If I have an electric heater and I stop using it — this will lower the demand on the electric grid, and accordingly some plant that is supplying electric to the grid will be ramped down. The plant that is ramped down will be the one with the largest fuel cost (i.e., marginal cost of operation). It won’t be a wind turbine, hydroelectric, or solar because they have no fuel cost. The energy saved will be the natural gas that is not needed in a gas peaking plant. In other words, in thinking about the carbon footprint of an electric load we should not look at the average carbon content of the grid, but rather the carbon saved or used when the load is decreased or increased.

A natural gas peaking plant has an efficiency typically of 30-42%. Let’s just call this 36%. At 36% efficiency a peaking plant would need to burn 9.14 cf of natural gas, which then has a carbon footprint of 1.1 lbs. In other words, no matter how clean the overall electric supply is for Maine or any other region — the marginal change in carbon emission when you increase or decrease the electric demand is 1.1 lbs of CO2. I would argue that this figure of 1.1 lbs/kWh is the relevant metric to use for deciding whether to use electricity or a fossil fuel to produce heat.

How do the above calculations change if this figure is used instead of the one used earlier (0.53 lbs/kWh)? With this carbon footprint for electricity, our Table above changes.

With this view, natural gas remains the best option for lowering carbon emission. The next best is the electric heat pump. Both propane and home heating oil still have higher carbon emission than an electric heat pump. The worst is resistive electric heat.

This view will not be popular — and many intelligent, committed advocates of sustainability will disagree. But I believe this is the correct way to think about this. Note that if the heating COP of the heat pump was higher — say 3 rather than 2 — then the heat pump would have a lower carbon footprint than any of the fossil fuel options — even when using electricity produced from burning natural gas in a peaking plant. And that would be the same in any state. Here in rural ME I don’t have the natural gas options — so even with COP = 2, the mini-split heat pump is my best option for lowering carbon.

I believe in just a few more years we will see new heat pump technology that does achieve a COP of 3 or higher over a wide range of operating temperatures. When that happens I will be a strong advocate of heat pumps — subject of course, to a cost/benefit analysis. This will be the subject of my next post.