At the 2007 GreenBuild Conference the USGBC released the results of their first major study of energy consumption by LEED-certified buildings. Then they presented conclusions from the now infamous study conducted by the New Buildings Institute (paid for by the USGBC and EPA) which, based on data “volunteered by willing building owners” for only 22% of the eligible buildings certified under LEED NC v.2, concluded that LEED certified buildings, on average, were demonstrating the anticipated 25-30% savings in (site) energy.

NBI’s analysis and conclusions were subsequently discredited in the popular media by Henry Gifford and in the peer-reviewed literature by me [see IEPEC 2008 and Energy & Buildings 2009]. NBI’s analytical errors included:

- comparing the median of one energy distribution to the mean of another;

- comparing energy used by a medium energy subset of LEED buildings with that used by all US commercial buildings (which included types of buildings removed from the LEED set);

- improper calculation of the mean (site) energy intensity for LEED buildings and comparing this with the gross mean energy intensity from CBECS;

- NBI looked only at building energy used on site (i.e., site EUI) rather than on- and off-site energy use (i.e., source EUI).

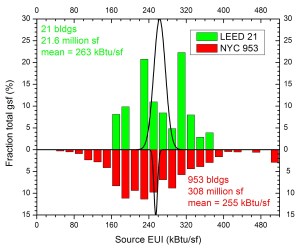

To NBI’s credit they made their summary data available to others for independent analysis with no “strings attached.” In the end even the data gathered by NBI, skewed towards the “better performing” LEED buildings by the method for gathering data, when properly analyzed demonstrated no source energy savings by LEED buildings. LEED office buildings demonstrated site energy savings of 15-17% — about half that claimed by NBI, the difference being associated with NBI’s improper averaging method. This site energy savings did not translate into a source energy savings because LEED buildings, on average, used relatively more electric energy, and the off-site losses associated with this increased electric use wiped out the on-site energy savings.

The lack of representative building energy data was addressed in LEED v.3 (2009) by instituting a requirement that all LEED certified buildings supply the USGBC with annual energy consumption data for five years following certification. Never again would the USGBC have to publish conclusions based on data volunteered by 1 in 5 buildings. Expectations were high.

But what has this produced? The USGBC has learned from their experience with NBI — not to hand over such an important task to an outside organization because you can’t control the outcome. NBI’s analysis was scientifically flawed — but it was transparent, and such transparency gave critics ammunition to reach different conclusions. Nowadays the USGBC simply issues carefully packaged sound bites without supplying any details to support their conclusions. There isn’t even a pretense of conducting scientifically valid analysis.

Consider the most recent claims made by the USGBC at the 2013 Greenbuild conference, summarized by Tristan Roberts in “LEED buildings above average in latest energy data release.” Roberts asserts the following:

- The USGBC has received energy data from 1,861 certified buildings for the 12-mos period July 2012 – June 2013;

- About 70% of these were certified through LEED-EBOM (existing buildings);

- 450 of these buildings reported their data through the EPA’s Portfolio Manager;

- the “building-weighted” (or un-weighted) average source EUI for these 450 buildings is 158 kBtu/sf;

- this average is 31% lower than the national median source EUI;

- 404 (of the 450) buildings above were eligible for (and received) ENERGY STAR scores;

- the average ENERGY STAR score for these 404 buildings was 85.

In addressing the above claims it is hard to know where to begin. Let’s start with the fact that the USGBC only provides energy information for 450 (or 24%) of the 1,861 buildings for which it has gathered data. Is this simply due to the fact that it is easier to summarize data gathered by Portfolio Manager than data collected manually? If so I willingly volunteer my services to go through the data from all 1,861 buildings so that we can get a full picture of LEED building energy performance — not just a snapshot of 24% of the buildings which “self-select themselves” to benchmark through Portfolio Manager. (The EPA has previously asserted that buildings that benchmark through Portfolio manager tend to be skewed towards “better performing” buildings and are not a random snapshot of commercial buildings.)

Next, consider the “un-weighted” source EUI figure for the 450 buildings. This is a useless metric. All EUI reported by CBECS for sets of buildings are “gross energy intensities” equivalent to the gsf-weighted mean EUI (not the un-weighted or building-weighted mean EUI). This was a major source of error in the 2008 NBI report — leading NBI to incorrectly calculate a 25-30% site energy savings rather than the actual 15-17% site energy savings achieved by that set of LEED buildings.

Consider the assertion that the 158 kBtu/sf source EUI figure is 31% lower than the median source EUI (presumably for all US commercial buildings). To be correct this would require the median source EUI for all US commercial buildings be 229 kBtu/sf. This is rubbish. The best way to obtain such a median EUI figure is from the 2003 CBECS data. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) does not report source energy figures in any of its CBECS reports. But the EIA does report site and primary electric energy used by buildings, and these may be combined to calculate source EUI for all 2003 CBECS sampled buildings. This results in a median source EUI for the estimated 4.9 million commercial buildings to be 118 kBtu/sf. If you instead restrict this calculation to all buildings with non-zero energy consumption you find these estimated 4.6 million buildings have a median source EUI of 127 kBtu/sf — way below the 229 kBtu/sf figure asserted by the USGBC. This USGBC claim is patently false. Of course the USGBC may be referring to the median source EUI of some unspecified subset of U.S. buildings. By choosing an arbitrary subset you can justify any claim. And if you don’t specify the subset — well, the claim is nothing more than noise.

What about the average ENERGY STAR score of 85? Is this impressive? The answer is no. Even if you believed that ENERGY STAR scores were, themselves, meaningful, such an average would still mean nothing. ENERGY STAR scores are supposed to represent percentile rankings in the U.S. building population. Since there are 4.8 million buildings, by definition we would expect 10% of these (or 480,000) to rank in the top 10% and we would expect another 480,000 of these to rank in the bottom 10%. That means that if 1,861 buildings are chosen at random from the building population, we expect 10% of these to have ENERGY STAR scores from 91-100. Similarly, we expect 30% of these (or 558) to have ENERGY STAR scores ranging from 71-100. Guess what — the average ENERGY STAR scores of these 558 buildings is expected to be 85. Only those who are mathematically challenged should be impressed that the USGBC has found 404 buildings in its set of 1,861 that have an average ENERGY STAR score of 85. If you cherry pick your data you can demonstrate any conclusion you like.

And, of course, these 1,861 buildings are not chosen at random — they represent buildings whose owners have a demonstrated interest in energy efficiency apart from LEED. I would guess that the vast majority of the 404 buildings were certified under the EBOM program and have used Portfolio Manager to benchmark their buildings long before they ever registered for LEED. LEED certification is just another trophy to be added to their portfolio. No doubt their ENERGY STAR scores in previous years were much higher than 50 already. What was the value added by LEED?

I openly offer my services to analyze the USGBC energy data in an unbiased way to accurately asses the collective site and source energy savings by these LEED buildings. How about it Brendan Owens (VP of technical development for USGBC) — do you have enough confidence in your data to take the challenge? Which is more important to you, protecting the LEED brand or scientific truth?