The other day a friend emailed me a link to the EPA’s April 2019 report of its Review of the Energy Star Hotel benchmarking score. In a nutshell, after suspending Energy Star Certification for the last six months or so pending a review of its revised methodology, the EPA has issued a report saying their revised methodology is correct and they are resuming operations. But the statistics reported in this “Analysis and Key Findings” simply confirms what I have documented earlier in my book, that the Energy Star staff do not understand the difference between real trends and random noise.

On page 1 of their report the EPA Energy Star folks publish this table demonstrating how U.S. Lodging buildings have evolved between 2003 and 2012.

The EPA’s text accompanying this table says, “Between 2003 and 2012, the estimated number of hotel buildings in the United States increased by 14%. During that period, the average site EUI decreased by 3% while the source EUI increased by 7%.”

Presumably these statements are made in order to justify changes in Energy Star scores for Hotels/Motels — the building stock has changed so the relative ranking of a particular building with respect to this building stock will change. Unfortunately the two EPA claims are false.

The table they used to justify this statement is not for Hotels — it is for all buildings classified by CBECS as Lodging. This includes hotels, motels, inns, dormitories, fraternities, sororities, nursing home or assisted living, and “other lodging.” Moreover, when you include the EIA’s relative standard errors (RSE) for both the 2003 and 2012 statistics you find these differences are absolutely meaningless. In particular, the Site EUI figures for 2003 and 2012 in the above tables are uncertain by 17% (2003) and 8% (2012), respectively. The differences between the 2003 and 2012 SiteEUI are just as likely to be due to random sampling errors as they are real trends!

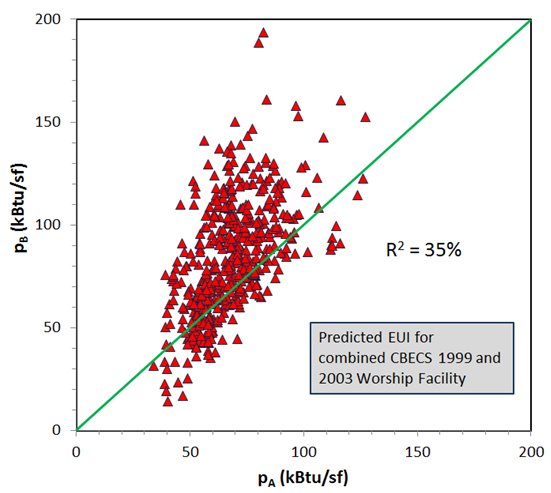

The EPA’s Hotel Energy Star model applies only to Hotels and Motels/Inns. When you look at these CBECS data for 2003 and 2012 you find even larger RSE that swamp any differences. The relevant statistics are shown in the Table below. The EIA did not calculate statistics for these two categories in 2003; these numbers are calculated by me using CBECS 2003 microdata. The EIA did perform the calculations for these categories in 2012. SourceEUI figures are calculated by me using the EPA’s 2012 site-to-source energy conversion figures (3.14 for electric). The percentages listed are the RSE’s for each statistic.

The number of Hotels increased by 50% from 2003 to 2012. During this same time the number or motels/inns decreased by 23%; their combined number showed no significant change and their combined floor area increased by 8%, hardly resolvable given the uncertainties in these quantities. The Site and Source EUI for these two types of facilities did not change in any significant way. The uncertainties in the survey far exceed the small changes in these EUI. It is impossible to know whether the changes reflect real trends or just sampling errors.

Joelle Michaels, who oversees the CBECS operation, is well aware of the limitations of the CBECS methodology. It must drive her nuts to see the Energy Star staff present such silly numbers and reports based on CBECS data.

This gets at the heart of my criticism in my book, Building Energy Star scores: good idea, bad science. The numbers employed by the EPA in their statistical analysis are so uncertain that in most cases they are studying noise and reading into it things that cannot be found. The science is sophomoric. It is the result of teaching a little statistics to people who lack the mathematical and scientific knowledge to use it properly.