This post may not be of interest to most my followers, but I hope it will be helpful to other Mitsubishi mini-split owners who use the Kumo Cloud App with WiFi to control their heat pumps.

Yesterday all six of my heat pumps began disconnecting from my WiFi and I have not been able to communicate with them until about 9:30 AM this morning. The details are strange and suggest to me that Mitsubishi has pushed some firmware update to these six devices that prevented them from connecting to my WiFi until mid-morning. As of this moment they seem to have restored their network connection — but there is no communication from Mitsubishi that explains what is going on.

What follows are more details of my experience. If you don’t own Mitsubishi mini-splits or use Kumo Cloud you probably won’t be interested in reading on.

I have six Mitsubishi mini-split heat pumps that are all connected to my network with WiFi adaptors that communicate using the Kumo Cloud App. Apparently Mitsubishi is in the process of rolling out a new app to replace Kumo Cloud. They call it Comfort by Mitsubishi Electric. If you go to the Apple App store and try to download Kumo Cloud you will get this new app, instead.

I have updated to the new app on my ipad, but on my iphone I did not update so that I still have the original Kumo Cloud App.

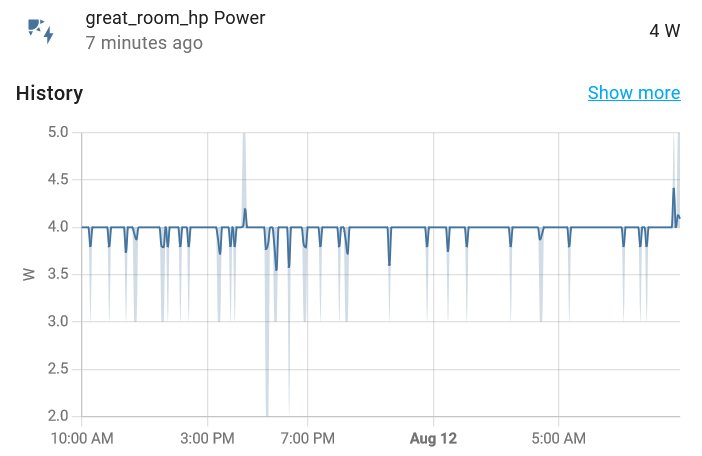

My Home Assistant program actually uses a Kumo Cloud integration to control/monitor my heat pumps over my local area network — uses the ip addresses and Kumo protocol to communicate with them without going out to the cloud. So even when my ISP is down and I have no internet connection, Home Assistant is still able to communicate with my six heat pumps — though the cloud apps on my ipad and phone do not have communication.

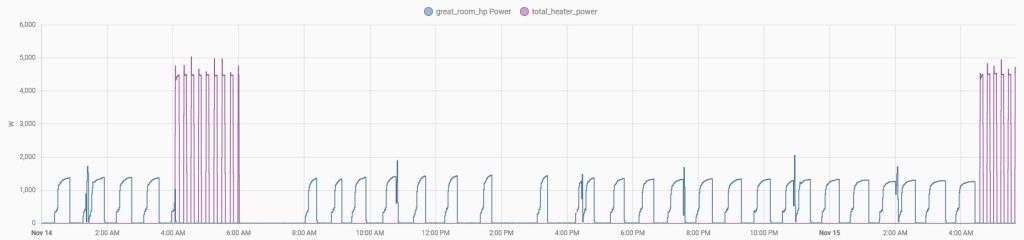

Yesterday Home Assistant lost its connection to all six of my heat pumps. I re-loaded HA, I rebooted HA, I updated HA, I rebooted the heat pumps — nothing fixed my connection. My Kumo Cloud app suggested all HP were off-line. I updated the App on my ipad to the new Comfort App, and after some time (a few minutes) it reported the HP as being disconnected from the network.

All six heat pumps have been assigned static ip addresses. I tried pinging them and they would not respond. Other devices on my network continued to work properly.

I rebooted my Deco X-20 access points. I rebooted my pfSense router. Nothing I did could get these six heat pumps to connect to my network. I spent about 3 hours this morning messing with all this.

Then, about 9:30 AM, the heat pumps began to connect to my new Comfort App. Several of them could be controlled with the new App. Others showed up, but the App said they were “off.” I see no way in the App to turn them “on.” I don’t know what off means — but the app is giving me no control of them.

I found that I could ping all six of the heat pumps again. I re-loaded my HA Kumo Cloud integration and all six heat pumps re-connected to HA. I can control them and read their parameters and HA seems to be re-connected as it should be.

But the Comfort App still shows two of the heat pumps as “off”.

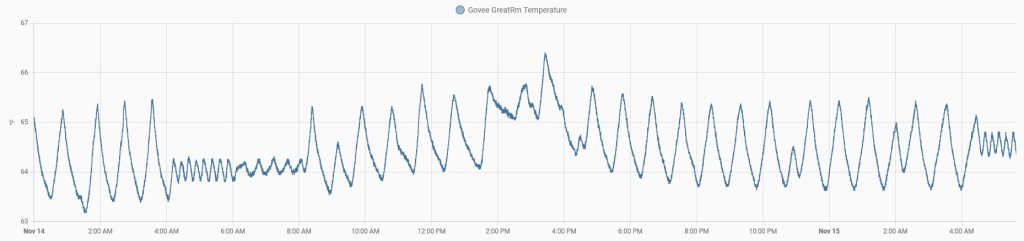

And, I am not home free yet. The heat pumps are still disconnecting and re-connecting to my network. Mostly they are connected, but every now and again when I check, one or more is disconnected.

I don’t know what is going on, but this roll-out by Mitsubishi is a disaster. Their Comfort App sucks. Whatever changes they have made to their WiFi boards has bugs — and there seems to be no information provided to consumers to explain what is going on.

Coincidently, my heat pump installer (Dave’s Appliance) had a crew next door working on my neighbor’s heat pump. I stopped over and asked the service tech if he could explain what was going on with the WiFi communication. He said they are getting lots of complaints from customers but no explanation from Mitsubishi. Mitsubishi tells them that there will be erratic behavior for the next couple of months.

This is simply unacceptable.