I have to begin by making this disclaimer — there are many issues involving cost that I cannot address. I don’t install or maintain hvac systems. I am the wrong guy to provide cost estimates for many things. What I can do here is compare the fuel costs and some capital investment costs for different heating systems that I have purchased — based on my limited experience.

The single thing I bring to this discussion is that I have, I believe, determined the average heating COP for the Mitsubishi heat pumps used in my house and cottage. This COP = 2 is different from the aspirational numbers that are supplied by those who sell and promote heat pumps. I don’t know of other studies that really nailed this.

Fuel Cost

First, let’s talk about fuel costs. Heating a residence involves heating the building. This heat has to come from some source of energy that you typically have to pay for. Here I will compare my heat pumps with three kinds of alternative heating systems: 1) electric baseboard heat, 2) through the wall propane heater, and 3) a home-heating oil furnace or boiler.

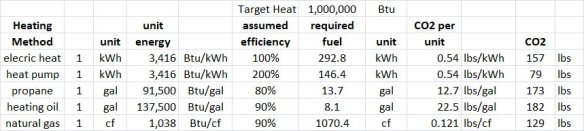

In my earlier post I provided a table with various assumptions regarding the fuel required for each of these systems to deliver 1,000,000 Btu of heat. Let’s now talk about fuel cost. This is very specific to location — my electric cost in Bristol, ME is nearly double what it was in Oberlin, OH. In OH I heated with natural gas. I don’t have access to natural gas here in Bristol, ME — only propane and home heating oil.

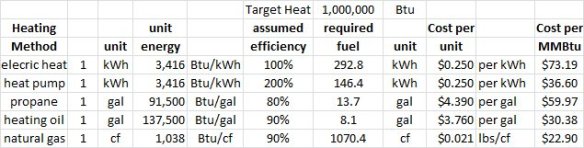

I am paying $0.25/kWh for electricity here in ME. This charge is always increasing, and who knows what it will be in a few months owing to the tariff war with Canada. The actual billing formula is complicated, but if you take my monthly bills and divide by the number of kWh I purchased for many months it averages to this.

And I am billed $5.09/gal for propane by my local supplier. This is not representative — I use very little propane and the per gallon price is high because of that. If I used 300+ gallons a year the price from my supplier changes to $4.39/gal. The maine.gov web site lists the statewide average prices (as of March 10) for propane and home heating oil to be $3.53 and $3.76. For my table below I will use $4.39/gal for propane and $3.76/gal for home heating oil.

While natural gas is not an option for me in rural Maine, it clearly is the dominant heating fuel in much of the USA, and is available in Portland and other larger cities here in Maine. The billing formula for natural gas is complicated, but the maine.gov web site lists typical February gas bills for residences in five areas that use 149 therms of gas (1 therm = 100 cu. ft.). If I average these prices I obtain $2.14 per therm or $0.021 per cf of natural gas.

The above numbers are folded into the tables that I posted earlier to yield the table below that shows the relative cost to produce 1,000,000 Btu of heat using different heating systems. The last column shows the cost per million Btu of heat delivered.

Clearly natural gas is the cheapest option, by far, with respect to fuel costs. This option is not available to me here in Bristol, ME. Of the options available to me, home heating oil at $30 (per million Btu) would have the lowest fuel cost, with the heat pump at $37 being next. Higher yet is propane at $60 (or $69 using the price I am actually paying), with electric resistive heat highest at $73 per million Btu.

So based simply on fuel cost, the electric heat pumps are the cheapest heating option available to me — though I have not considered a wood stove.

Capital Investment

I don’t have the expertise to discuss the capital costs for all of the possible hvac systems available. But I can speak to what I actually paid to install heat pumps at my house and cottage, and what I paid to install a through-the-wall propane furnace for my cottage. And, I have installed base board electric heat in my house.

My 1000 sf cottage has a very open architecture and my centrally-located, through-the-wall propane furnace does a wonderful job of heating it in the winter. (See earlier post for more information.) The furnace is a Rinnai EX22 that delivers heat at a maximum rate of 16,560 Btu/hr. The manufacturer claims 80% efficiency. This system cost me (2021) $4,700 to have installed, along with the propane lines and tank that support it. It is difficult to know how long it will last, but it is robust and I see lots of older units still in service. I will estimate the useful life to be 15-20 years.

I also had two Mitsubishi, low-temperature, mini-split heat pumps installed in the cottage, one a 6 kBtu/h size and the other a 18 kBtu/h unit. They both dump their air into the same space (from opposite ends of the cottage). In the heart of winter I run them both, but I have on occasion staged their use, using only the smaller or larger unit depending on the outside temperature. (I figure one unit will run more efficiently when not competing with the other to control temperature.) The invoice for this project was $8,921. Efficiency Maine provided a $1200 rebate. So my net cost was $7,721.

It was not necessary to install both the propane furnace and the heat pumps. I did this mainly so that I could study heat pump performance. I wanted a back up system in case the heat pumps failed in real cold weather and also an alternative if we lost power. Propane alone would have been sufficient.

To find the economic savings provided by my cottage heat pumps I first have to determine the annual energy required to heat the cottage — and that, of course, will vary from year to year. Since September 1, 2024 the cottage has been exclusively heated with the heat pumps with a constant set temperature of 67oF. From Sep. 1 through Mar. 16 my cottage heat pumps have used 2222 kWh of electric energy. At a price of $0.25/kWh this has cost me $556. We still have another 4-6 weeks left in the heating season. To account for the remaining energy (and I will confirm this later this year) I will multiply this number by 7/6. This puts my heat pump heating energy cost for this heating season at about $650.

Using numbers in the above table I can then calculate what it would have cost me to heat with resistive electric or propane. Resistive electric would have cost me double this or $1,300 and propane (at the $4.39 price) would have cost me $1,070. At $5.09/gal, the price I actually pay the cost of propane, the annual cost would have been $1230. (The projected annual use is 242 gallons which does not qualify for the lower price.)

Based on the above numbers, the annual savings for heat pumps as compared to electric resistive heat is $650 and the annual savings as compared with propane is $416 or $582, depending on whether I use the lower or higher propane price. Of course, the heat pumps required more capital investment and are expected to have only a 10 year service life.

I don’t actually know what it would have cost me to install electric baseboard heat in the cottage. At Home Depot an 8-ft long, 2 kW baseboard heater sells for $130. I would probably need to install two of these along with five or so 4-ft. models ($67 ea.). I would need to run appropriate electric circuits and add thermostat control. I did all the electrical work in my cottage and could do the wiring for these — but an apples-to-apples comparison requires I get a price for installation. Let me defer this for now.

The heat pump installation cost me about $3,000 more than did the installation of the propane heater. With a fuel cost savings of $416/year, the simple payback time (for the additional capital cost) is 7.2 years. With the higher propane price the savings is $582/year, the simple payback time is 5.1 years.

And, of course, the heat pumps provide me with cooling during hot humid summer nights. This is not so important in the cottage as it is located on the shore of the Pemaquid River where their is more summer wind. But this is of some importance in our house which is farther inland.

I don’t know what to say about maintanence costs. So far my installer (Dave’s Appliance) has provided service without any additional charges. The manufacturer’s warranty is 7 years and I have not experienced problems with the heat pumps. That, of course, will change. But so far I have not had any maintenance costs.

There are many more issues to discuss, but this post is getting too long. In future posts I will discuss the cost/benefit of the heat pumps in my house, share data on the temperature control (which is significantly more stable with electric baseboard or propane heat), and share data that I used to learn the average COP was equal to 2.