A few weeks ago in my post I described how one of my four Mitsubishi mini-split heat pumps was using excessive energy. Today’s post provides additional information about that. Apparently the excessive energy is by design! For background please revisit my August 12 post.

Just a quick recap — In the last three years I have had four, low-temperature, mini-split heat pumps installed on my property in Maine. The oldest of these is a 15 kBtu/h unit that is installed in my house living room. The model number for its outdoor unit is MUZ-FH15NA. The other three units were installed over the next two years. Their outdoor units have model numbers: MUZ-FS06NA, MUZ-FS18NA, and MUZ-FS06NA. (Apparently the “FS” models are improved over the “FH” models.) All four compressors use R410A refrigerant.

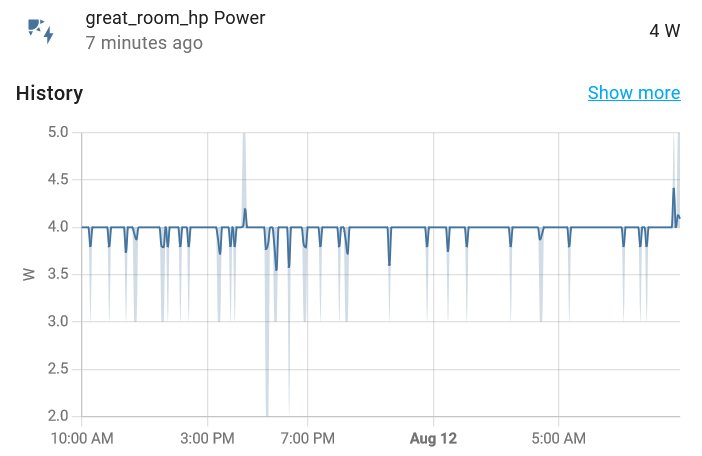

These units have seen minimal use since the beginning of May. On rare occasions we have used them for a bit of cooling or heating. They have simply remained in standby mode for nearly 120 days. Three of these use 3-4 W of continuous standby power but the oldest, the 15 kBtu/h unit, particularly during the night, experiences 70W power spikes every two hours or so that last for about 10 minutes. This causes this unit to use about 0.2 kWh per day more energy than the other three. For three months I have been seeking to understand what is going on.

Back in June I emailed my installer, Dave’s Appliance, questions about this performance including graphs and other details. I have always found Dave’s to be extremely helpful. They could not explain what was going on so they passed the information along to their Mitsubishi support team. A couple of months went by with no answer.

I pestered them some more. Finally, in mid-August, two technicians from Dave’s drove the 50 miles from Winthrop to my house to make measurements on the compressor while on the phone with their Portland Mitsubishi tech support. With the travel time, these guys spent a half day addressing my issue. The only measurements they made were to confirm that a certain thermistor had the correct value.

One of the techs who came to my house was Ean Laflin, the heat pump service manager with Dave’s Appliance. After he was done troubleshooting and speaking with Mitsubishi he explained that there was a 70 W heater in the compressor, and that the control board turned it on whenever the ambient temperature was below 68F. Presumably after the heater ran for 10 minutes the temperature of the thermistor rose above the set point causing the heater to turn off. (It is my impression that there is oil in this compressor, and this heater is intended to keep the viscosity of this oil low so the compressor will start easily when called upon.)

But this begs the question, why would this heater be activated when the ambient temperature ranges from 60F to 68F? I could see the need to heat the oil during the winter. But in my part of Maine from May – October the ambient temperature is usually above 68F for much of the day and usually drops below 68F late at night. For nearly four months I have not needed this heat pump yet the heater keeps using energy, night after night. The only way I can avoid this is to shut off the circuit breaker. This is obsurd!

So why doesn’t this same thing happen with my other three heat pumps? Ean tells me that the control board on these slightly newer models is shipped with a jumper that can be set so as to disable this feature — apparently this is the default setting. He can change the jumpers on the other three heat pumps so that all four of my heat pumps run this heater and waste energy. But there is no jumper to change on my Living Room heat pump to reduce its standby power to 3W like the other three heat pumps.

I conclude from this that Mitsubishi, after shipping thousands or perhaps millions of heat pumps with this control strategy determined it was not necessary and “improved” the next generation of control boards. The only way to “improve” my heat pump would be to install a new control board. I recognize this is not a cost effective way to save the $15/year wasted by this heater.

Which leads me to my last point. Each one of my four heat pumps is connected to the internet and can be controlled using the Kumo Cloud App. Why can’t Mitsubishi download updated firmware over the internet to fix this bug? Hundreds of millions of devices (phones, etc.) that only cost a few hundred dollars can receive updated firmware over the internet. Why can’t Mitsubishi figure this out for heat pumps that cost many thousands of dollars? The technology really needs to be updated.